Before it is too late

In Yannick Pasquet’s special report — “Tell what happened to us”: the last death camp survivors — they described what was done to them and to so many millions of others during those dark years. “We are the very last generation” who can personally testify to the horrors, said 86-year-old Evelyn Askolovitch, who was four when she was taken from her home in France to the camps. Some, like 97-year-old Austrian Erich Richard Finsches, feel that the need to keep the memory alive is even more urgent now, because “these are dark times” too.

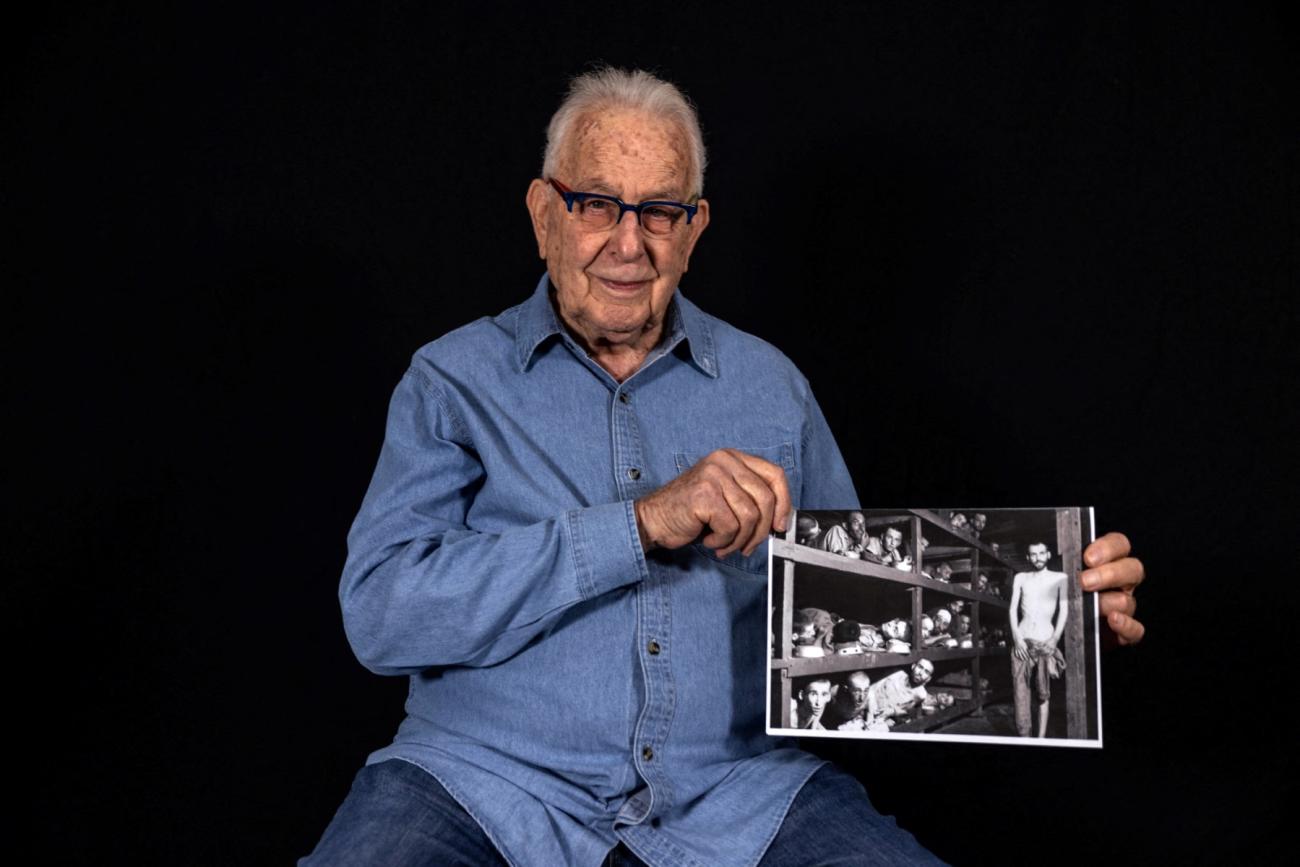

The idea was to document, film and photograph as many survivors as possible and give them the chance to speak while they still can, said Samantha Dubois, AFP’s Europe Photo Editor, and Deborah Pasmantier, a Deputy Editor-in-Chief in charge of long reads. The youngest of the survivors AFP spoke to were actually born in the camps. They are now in their eighties; the oldest was nearly 110. Some feared the Holocaust would be forgotten — “drowned out” by the weight of history or by the constant stream of social media.

The power of the gaze

AFP journalists on five continents interviewed the survivors between November 2024 and January 2025. Often, they had their portraits taken in front of walls covered with pictures of their descendants — a living, breathing rebuke to the Nazis’ murderous madness that swept away six million Jews. “I wanted them to be photographed straight on, so they were looking directly at us — so we were exchanging not just a look but their personal history — how they had lived their lives as survivors of the unimaginable,” said Dubois, who drew up the guidelines for how they should be shot.

“This is our common history — we are the children of this history — and of what it brings us back to today with the rise of anti-Semitism and populism in Europe and beyond,” she added. “It was also important that they were with their families, because that represents transmission, continuity and the force of life.”

AFP photographers asked the same four questions to each survivor, starting with their deportation; what they have been able to pass on, and what will happen to that legacy once they are gone. Finally, we asked about their hopes and fears for those who come after them.

Tears and silence

Most of the survivors had been interviewed several times before. Naturally, questions arose about the usefulness of putting them through such trauma again to ask about what is already well documented. But Holocaust historians we consulted stressed the importance of direct testimony at a time when soon no one will remain who was actually there.

“Our approach was to focus on them as individuals, asking open questions to let them choose what they wanted to say — whether for the first or last time,” said Pasmantier. And the survivors went far deeper in their replies than we ever expected.

“At this historic turning point,” when many may soon be gone, “we also wanted to explore how younger generations are taking on this legacy,” said Pasmantier. Especially “at a time when anti-Semitism is rising in ways we haven’t seen since the end of the Second World War — with some even questioning the facts of what happened.”

“The hours of recordings were difficult to listen to,” Pasmantier admitted. “The tears, the silences, the depth of the pain. But there were also happy childhood memories that surfaced unexpectedly, as well as the love and affection between them and their grandchildren.” There were touching exchanges too, she said — as when South African survivor Ella Blumenthal told AFP’s Gianluigi Guercia: “You really look like my cousin from Paris.”

Some found it very hard to speak, but insisted on doing so — “because we must”. Others, to Pasmantier’s surprise, were upbeat, even joyful, speaking of “the miracle of life, despite everything”.

'Too hard'

There was also a “really intense moment for everyone” when 88-year-old Petr Polacek, born in Czechoslovakia, told Mabromata about his time in the Theresienstadt camp. “We realised his daughter was upset — she was hearing part of his story for the very first time,” and asked why he had never told her before.

'The art of surviving'

“Every now and then”, said AFP’s South Africa-based photographer Gianluigi Guercia, he listens again to the recording of his conversation in Cape Town with Ella Blumenthal, who lost her entire family in the Holocaust. “She had the greatest impact on me,” he said. “I was deeply moved by how someone who went through such events — surviving Auschwitz and Majdanek — could still be so full of life, even at 103.

“She kept referring to ‘the art of surviving’ — and indeed, she was an artist at it. One of the stories she shared was particularly moving: she and her niece were inside the gas chamber, waiting to be killed. They had already said goodbye to one another, but someone realised they were in the wrong group. They were called out, and their lives were spared. Such a story puts everything into perspective,” Guercia said.

Guarding the memory

Athens Bureau Chief Yannick Pasquet — who, in her previous post in Berlin, covered the last Nazi trial held there — had the task of weaving these testimonies together. In a poignant twist, there were no Greek Jewish survivors left from Thessaloniki able to speak to her — even though they once formed the majority of the city’s population. “The idea was to make each testimony personal, so that we could relate to something universal about the human condition,” she said.

One phrase from Marta Neuwirth — who was 15 when she saw women calmly led into the gas chambers — immediately stood out for Pasquet: “How did the world allow Auschwitz?” “She gave voice to the fundamental question that has haunted the world since 1945,” Pasquet said.

The story of Polish-born Canadian Pinchas Gutter also left a mark on her. The 92-year-old spoke about not being able to remember his twin sister Sabrina’s face. She was murdered in Majdanek when they were 11. “All he remembers is her beautiful blonde braid. That said everything. Everyone in the world can relate to a testimony like that.”

“Reading all of these testimonies took time and was emotionally tough,” Pasquet said. “But at the same time — despite all they endured, and despite the world’s current state — every one of these survivors carried a message of hope.”

Explore our coverage. Get an AFP News free trial.